Assessment

Why is assessment important?

Our multidisciplinary assessment provides a comprehensive formulation of the child’s strengths, difficulties, needs and protective factors – across the whole range of mental health disorders. We consider information from different sources and the child's presentation in different settings, such as home, at school, and in our clinic. We use the formulation to develop our care plan, which may address a range of problems e.g. mental health, educational engagement, and home needs. As part of the assessment, we may complete:

›› Individual assessment of attachments and identity

›› Individual psychometric assessment of abilities and emotional profile

›› Specialist neuropsychological and social communication assessment

›› Family environment review through interviews with caregivers and relevant professional networks

›› Educational attainment assessment and current school functioning by talking to teachers

Process of assessment

1. Pre-assessment

Before our assessment, we ask the parents/carers, the teachers and the child if old enough to fill in an online standardised screening questionnaire. This gives us very good preliminary information before the assessment because it highlights possible areas of concern from different points of view, so we can offer you a more focused and personalised assessment on the day. In addition, before your assessment, we will have reviewed all the relevant background information that we have access to (e.g., adoption records, health reports, previous CAMHS involvement, etc).

2. Day of the initial assessment

In our assessment, which is usually a morning session, our multidisciplinary team will see the parents and the child, and maybe some professionals who wish to attend, together and separately.

Introductions

On the day of assessment, all the members of the team that will be involved in the process are present at the beginning for introductions, greet the family, and explain the set-up for the day, and also what will happen in the following weeks before we produce a report. This can happen either in a face to face in the clinic, or via Teams.

Interview with the child

Focusing on the above, after introductions, one of our clinical psychologists will either take the child to a separate clinical room if in situ or will remain on the screen to interview the child and make clinical observations.

The child's session is adapted to best suit the child's age, developmental stage, and individual needs ( for example, sessions with younger children are generally more play-based, while a session with a teenager may be structured in a similar way to an interview with an adult). We use different formats for the interview, depending on the age of the child:

§ For very young children this might be not be focused on gathering information about, for example, their inner world, so much as observing their ability to understand and use language or social conventions etc. The older the child is, the more we can ask them questions, in an interview tailored to their developmental age and stage, to access their internal world, their thoughts and feelings and their current symptoms.

§ Older primary school-aged children and certainly teenagers are often the best informants about their emotional behavioural concerns and worries. So, we would want to talk to them as part of our broader assessment package in a structured interview.

Observations of the child/young person

In the face-to-face appointment in the clinic, we make a series of observations while conducting the interview around things like mood, the use of language, social engagement, their ability to sustain and maintain attention, their energy levels and motor activity. While we do a video-based interview with the child, then we can still do many of these:

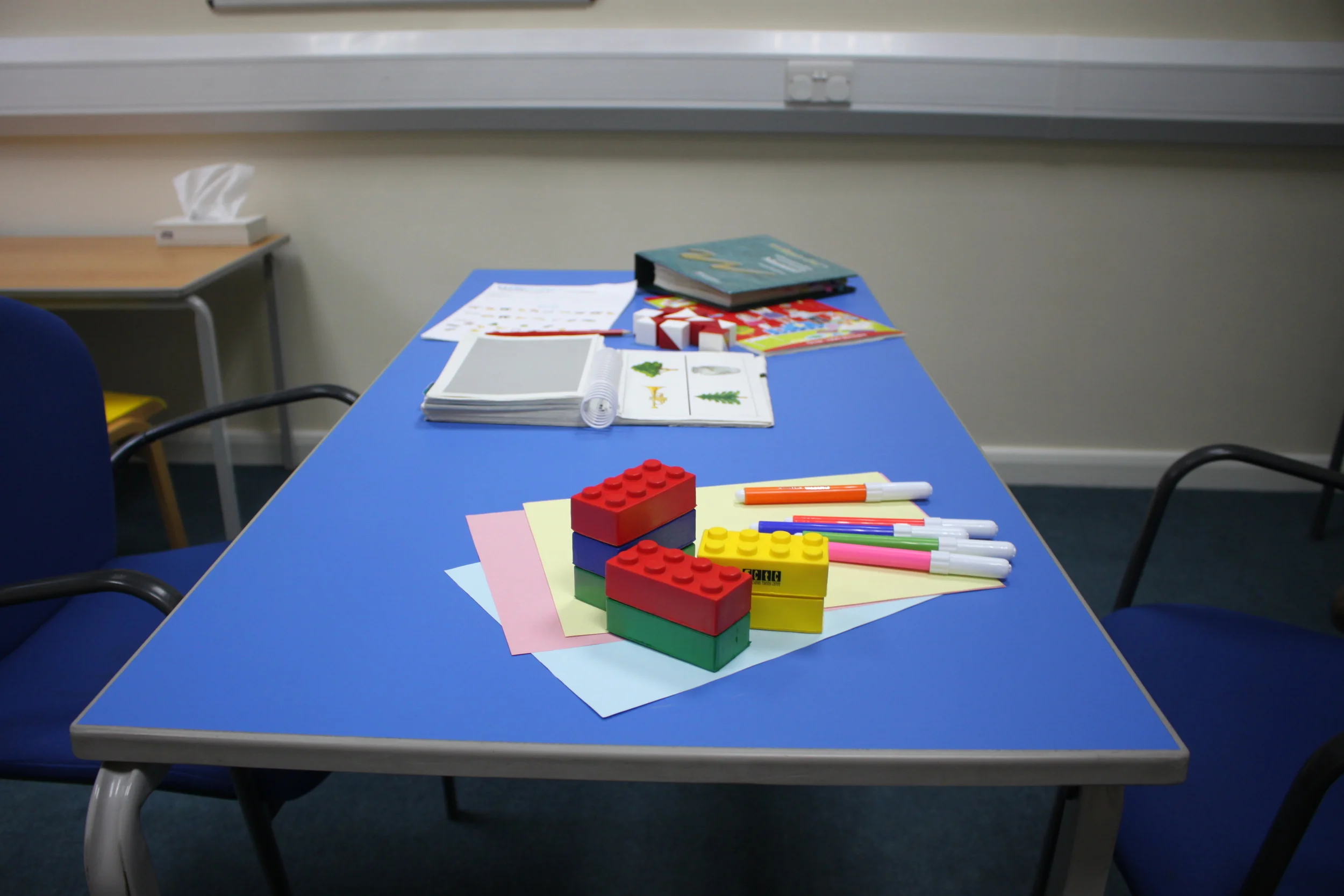

§ For younger children, we can observe the child engaged in an activity, possibly with an adult so we get a chance to look at some of these aspects. We ask parents to choose the kind of things they would be most likely to engage with. Examples might be, for a younger child, building with blocks, or with Lego, doing drawing to make a favourite animal or time; some may be happy to play with dolls or animal figures.

§ For older children and teenagers, it is helpful to observe the way of interaction, maybe not while playing a game (depending on their developmental age and stage, but parents will know best) but to have a discussion about some “hot topics”. For example, if you were to win £100 as a family to spend on a treat, what would you choose as a family?

Further assessment of the child/young person

A few of the tests that we administer in the clinic require to have the child sitting child face-to-face to us. This includes cognitive or neuropsychological assessments to help tailor education (e.g. WISC, NEPSY, etc), or ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) for Autism Spectrum Disorders. This is routinely planned in the face to face assessments and may be one of the indications for the child to have to be seen in situ. If this is not possible (e.g. due to distance), we can make recommendations for them to be completed by psychologists in their local area.

Interview with the parents/carers

While the child is with our Clinical Psychologist, one of our Child & Adolescent Psychiatrists (medical doctors) will interview the parents or carers. If childcare cannot be arranged, we are flexible and can do the interview another day of their convenience.

In the parent interview, our assessor will focus the assessment around the information we have already received and also widen the enquiry to see if there are any further issues that you want to raise on the day. We call these the 'Presenting Issues', and it is your chance to tell us your concerns in your own words.

3. Collateral history/other informants

As part of our assessment, we also gather collateral history from other informants like teachers, previous therapists, etc.

4. Report production

After we have gathered all the background information, undertaken all the interviews and observations, scored the validated questionnaires and have multidisciplinary case discussions, we produce a draft report with the formulation, diagnoses (if applicable) and recommendations.

As part of our commitment to involve parents and carers in the process, we send the initial report back to parents for comments and corrections, to make sure we understood everything right and that the parents view is reflected.

The final report will include:

All the factual information in which we base our conclusions: the revised parents/carers views, the child interview, psychometrics, interview with school, school observation (if needed), summary of previous records, results of the standardised questionnaires all the parties have completed, and any further psychological testing we have carried out.

The biopsychosocial formulation, which provides an account of what the issues are, where they may have come from (what specific aspects in this child’s pre and postnatal life may have influenced their development); what made these issues become a problems in this child’s life, or what made them worse (what triggered the onset or worsening of the problem); what things are likely to make any issues continue or get worse (what factors could stop thing improving on their own); and, importantly what strengths the child or family has, or what could help the family make things better (what the resilience factors are what could be done to maximise well-being).

Any mental health diagnoses we have identified if any, as well as ruling some out (differential diagnoses). Sometimes ruling out what is not a mental health issue can be as important for a child and their family, as identifying something new.

Finally, this report will include recommendations for mental health, well-being, placement and education, as appropriate, some of which we might carry out, and some that may be better delivered by other services/agencies.

Case study

Lucas is a 15-year-old boy who was referred to the National Adoption and Fostering Clinic for a comprehensive assessment: he had longstanding difficulties with behavioural outbursts, lying to avoid responsibility, lack of empathy and poor emotional literacy. Lucas had also a long history of services involvement.

Lucas was born addicted to heroin (which his birth mother took during pregnancy) and stayed in the special care baby unit for 23 days. Both birth parents had, apart from substance misuse problems, learning difficulties, forensic history and significant mental health problems.

Straight from hospital, Lucas was taken into a very experienced foster family, who took care of him for 10 months. They already noticed he was a restless baby and that his temperament was irritable (prone to crying and difficult to soothe). At that point, Lucas was adopted and from day one, his adoptive parents noticed the same issues - that he would “scream not stop” and refuse physical contact. As he was growing, behavioural problems emerged: Lucas would hit other children, and was cruel to animals. His social development was always unusual: he did not greet, had poor imagination, repetitive play, and rigid with routines. His speech was very delayed: aged 5-7, only his parents could understand him and he had speech and language therapy from an early age until teenage years.

Lucas was referred to CAMHS at 5, and started “attachment work”- we could find no rationale for this other than he was adopted and no treatment aims. A therapist provided intensive psychotherapy for 5 years: 3 times a week for the first 2 years, 2 days a week for a year and once a week for the last 6 months. In the final therapy report, Lucas’ sleep problems, soling, smearing faeces, and making compulsive, strange and animal-like noises were noted but it was felt that his “early history prior to adoption may well have impacted severely on his emotional and cognitive development in ways that had been difficult to assess”. Aged 10, when his psychotherapy ended, he was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and was transferred to CAMHS clinics for medication monitoring. At this time, he had his first Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) assessment, in which a diagnosis was ruled out, despite plenty of evidence, because he was adopted.

On our assessment, Lucas told us “that he would rather have a spider crawl on his arm than go through the experience of therapy again”. His behavioural problems were as prominent as ever, being frequently excluded from school, but the parents had never received any evidence-based intervention to manage his extreme challenging behaviours. We found out that Lucas had very limited prosocial emotions: he did not experience guilt and remorse after he had hurt somebody, he could not feel empathy, he did not care about his performance and his affect was shallow and superficial. This was important to help us formulate what maintained his problems and inform the recommendations for the parents’ work. In addition, a clear neurodevelopmental picture emerged: apart from ADHD, Lucas was diagnosed with ASD [both issues that were likely to have been present in his birth parents]. This helped the parents understand some of his obsessions and rigidity, lack of reciprocity and non-verbal communication, as well as his fixations, which were beyond what a normal adolescent would present with. More importantly, it relieved the blame they had felt all these years when services and school had understood all the problems as part of “their attachment problems”. The family knew that attachment system gets activated at around 9 months, so they agonised with the question: “if he was in a good foster placement and he came to us at 10 months, what does it say about us if we could not develop an attachment?” But the answer was that most of his problems were set in motion before birth [e.g., very likely exposure to substance misuse and birth parental genetics].

Psychoeducation around ASD and the particular presentation of children with Limited Prosocial Emotions, all embedded in the formulation that took into account both genetics and the impact of opiates in the developing brain in helping the family move away from blaming themselves and helping their child. Likewise, school and other agencies could put in place measures to support Lucas develop his potential.

If you’d like to know more about the assessment process, you can contact us by telephone on +44 (0)20 3228 2546 or get in touch by email.